|

|

Transcribed

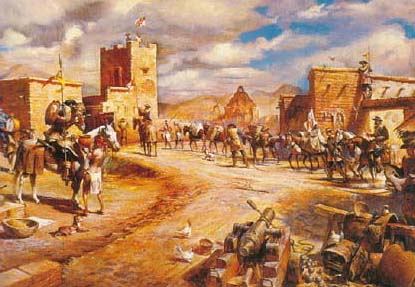

CAPTAIN JOSE DE ZUNIGA

Commandant Tucson Presidio

June 12, 1810

Report to Viceroy of New Spain

Your Excellency,

All of my soldiers, the settlers, and Indians of Tucson live in an area less than two miles square. The total population under my military charge comes to 1,015. This Tucson jurisdiction includes the Indian village of San Xavier Del Bac, ten miles away to the south, the Indian village at Tucson, and the Presidio with its settlers and troops. The rivers of this region include the Santa Catalina (now called the Rillito), five miles from the presidio, which seemingly arises from a hot spring at the base of the mountains and enjoys a steady flow for ten miles in it's northwesterly direction, but only in the few rainy seasons. It is thirty-four feet wide near its headwater. The now abandoned Pima mission at Tumacácori, and the Tubac Presidio stand empty after the tribes uprising.

When rainfall is only average or below, it flows noticeably above ground to a point well five miles north of Tubac and then goes underground all the way to the area of San Xavier Del Bac. Only during any years of exceptionally heavy rainfall does it water the flat lands between Tubac and San Xavier Del Bac.

We have no gold, silver, iron, lead, tin, quicksilver, copper mines, or marble quarries. Twenty-five miles from this Military Presidio is a large outcropping of lime which supplies us with all we need and whenever we need it for construction. We have no salt beds here.

Our major road connects Tucson with San Xavier Del Bac and Tubac. We have many other trails which we use only for stock raising and chasing the Apaches who regularly raid the area. No bridges have been built. We have no hostelries or inns. The only work here that is truly worthy of this report is the church at San Xavier Del Bac, ten miles from this Presidio. Other missions here in the north can only be called chapels, but San Xavier Del Bac is truly a church. It is ninety-nine feet long, twenty-two feet wide in the nave, sixty feet wide at the transit, which forms two side chapels. The entire structure is of fired brick and lime mortar brought by ox carts. The ceiling is a series of domes, and the interior is adorned with thirty eight full figure statues, plus three framed statues dressed in cloth garments, and innumerable angels and seraphim.

The facade of the building is quite ornate, boasting two towers, one of which is still as yet unfinished. The atrium in front extends out twenty-seven and a half feet. To the left of the atrium is a cemetery, with a domed chapel at the far end surrounded by a fired brick and crushed lime plaster walls, measuring eighty-two and a half feet in the circumference of it. A conservative estimate of the expense incurred to date in the construction of all that has been mentioned, plus the sacristy, the baptistery, and the other rooms, all of which are also domed, would be 40,000 pesos. The reason for this ornate church at this last northern most outpost of the frontier of New Spain is not only to congregate the Christian Pima Natives of the San Xavier village, but also to attract by its beautiful loveliness the unconverted Papagos and Gila Pimas beyond the frontier.

I thought it worth while to describe it in such detail because of the wonder that such an elaborate building could be constructed at all out here on the farthest frontier of the just and God given right of New Spain. Because of the consequent hazards involved, the salaries of all the Native artisans had to be doubled to keep them from running away during the night.

We have no local militia of cavalry or of infantry, but the settlers here band together during indian attacks and really do the same job. They are quite accustomed to using their own firearms and horses to help us defend the Presidio Fort and pursue the fleeing Apaches when we are short of troops. In fact, they are obliged to do so to hold title to land anywhere within five miles of the Presidio or their lands are confiscated. Their farmlands and the lots for their homes are given to them only under this condition, by order of the Royal Regulation of Presidios.

In return for this military service, they are also exempt from personal taxes to the government and to the church and are entitled to the spiritual ministrations of the chaplain without the financial obligation to support any parish. Two soldiers barracks are attached to this Presidio, one for the resident garrison and another to house the troops here on detachment from other Presidios. As to recruiting activities, we have five recruits attached to this company presently.

We pay no sales tax when we buy here at the Presidio. I do not know what sales tax is charged elsewhere. That information is available through José Pérez, the regions sales tax administrator. We pay no tribute. In tobacco taxes, we have paid out 2,210 pesos. We have no gold or silver mines and therefore are not subject to the royal twenty percent payments to the King in Spain. No money is spent on the administration of fiscal activities. The Presidio paymaster receives no extra pay for collecting the tobacco tax. The tobacco is sold either in the military company store or directly by the paymaster. The paymaster also administers all the revenue from the mails. No extra pay is received either by him or by the troops involved in carrying the mail from one military post to the next.

The population here spends 5,750 pesos a year at the company store on merchandise from Spain and 2,520 pesos more for the same purposes with a private merchant. Five hundred pesos are spent annually on merchandise from Asia and China. Three hundred pesos a year are spent on wax and cocoa. Cocoa, however, is replaced here by commercial chocolate, since no cocoa is available. We receive no products directly from Vera Cruz, Acapulco, or Mexico City, or get any smuggled goods. We produce 630 bushels of corn a year, and it sells at two and a half pesos a bushel. Wheat sells at two pesos a bushel, and our area harvests 2,980 bushels annually. Beans and other vegetables sell at four and a half pesos a bushel.

About 420 bushels are produced annually. Cotton is raised only by the Indians. With it, they weave a rough fabric for their own use. We grow no sugar, tobacco, cacao, vanilla, sarsaparilla, tabasco pepper, jalapa purgative, indigo, cochineal, campeche wood for dyeing, or wood for fine lumber. We have some 3,600 head of cattle, selling at three pesos a head. The sheep sell for half a peso a head, and we now have about 2,700. We raise no pork and no goats. The horse herd stands at 1,290 head, including the Presidio soldiers mounts, the settlers and the two missions.

We have 170 mules, thirty three burros, 65 oxen. Animal slaughtering accounts for over 300 beefs killed each year, including the 130 slaughtered at the expense of the Spanish Royal Treasury to maintain the peaceful Apaches. Two hundred sheep are slaughtered. A dressed beef sells at six pesos, a dressed sheep at one peso. Soap making accounts for 1,000 pesos spent annually by this population, including the soap needed to provision the garrison. It is difficult to estimate the quantity involved, since soap is sold here in bars and not by weight.

Over half of this soap is made here in Tucson and at San Xavier Village. The rest is bought in from Nogales. No brandy, whiskey or tequila is distilled. No gunpowder, chinaware or glass is manufactured. Four men here operate horse pack trains, there are no wagon trains. Two hundred are engaged full time in agriculture and stock raising, including the Indians who tend the fields and the livestock of their missions. Twenty four men work at the ordinary industrial trades.

In connection with government revenue, I have observed that all connected directly with the Presidio are exempt from all personal taxes. Why, then, do the privileged settlers not prosper more than they do? I believe this is their own fault. Since no demands are made on them, they lose all ambition. Even the most rustic Indian will double his efforts as the time approaches when his tribute is due. An artisan or laborer, whose wife is pregnant, will double his earnings to be able to pay for the approaching baptism celebration, or for the funeral celebration if his relative is dying.

Since the Royal Regulations of the King are in their favor, however, I am not saying that these settlers should be taxed. Why, too, is there not even an attempt at the mechanical arts and trades? At least weaving should be carried on here, when even the coarsest woolen and cotton fabrics must be brought in from New Mexico or all the way from Mexico City. I believe it is for lack of accomplished teachers in these arts and trades.

Tucson desperately needs a leather tanner and dresser, a tailor, and a shoemaker. These people could support themselves very comfortably here. Perhaps even more important would be a saddle maker, who could vary his trade by making cinches, leather jackets, saddlebags, saddle pads, cruppers, pack saddles, gun sheaths, and cartridge belts. With his shop right here in the Presidio Fort, he could fashion these items to the exact specifications of his clientele. A professional weaver could do very well for himself by making artistic blankets and serge cloth, as could a hat maker by fashioning new hats and cleaning and blocking the used ones.

These shops would not only offer the soldiers and settlers custom made articles, but would also serve as schools for apprentices of these same trades. I have also observed that there is very fertile land here. Why do the settlers not prosper when even neglected vineyards produce a bumper crop? They hardly allow the grape to mature properly before they are selling it, to say nothing of not experimenting with new vines and cuttings. All of this could be regulated by government control, and prizes could be offered to encourage both quantity and quality.

REPORT ON PERSONNEL OF THE ROYAL PRESIDIO OF SAN AGUSTIN AT TUCSON WHO HAVE FULFILLED THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE ROYAL DECREES OF OCTOBER 4, 1766, CONCERNING A BONUS FOR LENGTH AND CONSTANCY OF SERVICE, AND OF APRIL 20, 1815, CONCERNING TIME SPENT IN FIGHTING THE INSURGENTS.

Enlistment: Ildefonso Bojórquez - heretofore an unemployed resident of Tucson - born in the Presidio at Tubac in 1786 - parents Ignacio Bojórquez and Loreta Preciado - religion Roman Catholic - light brown hair - dark eyes - large nose - round face - light ruddy complexion —enlisted voluntarily as drummer boy to serve for ten years at this Tucson presidio beginning today, September 1, 1800, and signed with a cross before the witnesses Sergeant Juan Antonio Olivia and Salvador Gallegos, both soldiers of this company.

Notes:

Ildefonso Bojórquez has merited an additional monthly pay of six silver reales since September 1, 1815, for length and constancy of service.

He left Tucson to fight the Insurgents on the coast of El Rosario and the southern frontier of Spanish Sonora on January 23, 1811, where he is still assigned. This time counts as double for his length of service bonus and retirement.

José Miguel Burrola

Enlistment: José Miguel Burrola - heretofore employed as a laborer here - born here in Sonora in 1772 - parents Antonio Burrola and Vicenta Granillo - religion Roman Catholic height 5' 1" - black hair— dark eyes - ruddy complexion - sharp nose - scar on right leg - enlisted voluntarily during recruiting mission here at Tucson to serve for ten years at the Tucson presidio beginning today, July 4, 1797, and signed with a cross before the witnesses José Domingo Granillo, recruiting sergeant, and Luis Moreno, both soldiers of the Tucson Presidio.

Notes:

Corporal José Miguel Burrola reenlisted for five more years on March 7, 1808, and took the customary leave of two months at that time, as attested to by Antonio Narbona, Acting Commandant of the Tucson Presidio Fort at that time, and Antonio García de Tejada, Adjutant Inspector.

He served under Alejo García Conde in the famed battle of Piaxtla on February 8, 1811, against the Insurgent army of 7,500 men under the self-styled colonel Hermosillo. The Insurgent army was routed, lost all of its artillery and baggage, and left 600 dead on the field. Burrola's service is attested to by Alejo García Conde himself, Commander General of the Northern Provinces of New Spain at that time.

By July 1, 1812, he had engaged in twenty full campaigns and twenty-five briefer missions against the Apaches, with a total of 275 Apaches dead or captured. He has merited an additional monthly pay of six silver reales since July 4, 1812, for length and constancy of service. He left Tucson to fight the Insurgents on January 23, 1811, and he is still assigned to that mission. This time counts as double for his length of service bonus and retirement.

This site is copyrighted© and registered® TUCSON MUSEUM, TUCSON HISTORICAL SOCIETY - No part of the information or content found here may be reproduced or duplicated in any form whatsoever without the prior written permission of 'TUCSON MUSEUM, TUCSON HISTORICAL SOCIETY'. All rights reserved. You may not, except with our express written permission, distribute or commercially exploit the content. Nor may you transmit it or store it in any other website or other form of electronic retrieval system with the exception of 3rd party items and others contained within the website that are in the public domain and or except for educational purposes under U.S. Fair Use Copyright Laws and a link back and acknowledgement of the Tucson Museum is mandatory.